Tuesday, October 26, 2004

Quote of the day

For once, I'll also have a quote of the day:

The Western world is embroiled in a new religion which we cannot associate ourselves with.Archbishop Peter Akinola, reported by the BBC

Heb 1: alphabet

These are my very first notes on Biblical Hebrew. As a textbook, I am

using Lambdin's Introduction to

Biblical Hebrew, together with the U of London study guide for

the course "Foundations in Biblical Hebrew" (frankly, I have found

this study guide only marginally useful so far -- but I am still very

much in an early phase). I am using throughout this post a font bigger

than usual for clarity.

To do: print out Psalm 25 in Hebrew, along with a translation. Practice writing and recognizing the Hebrew letters; write them on flash cards.

Useful online reference: Learn to read Biblical Hebrew

Since it was not obvious for me to find how to type the Hebrew letters using the Tavultesoft Keyman keyboard with the Ezra SIL Unicode font just reading the docs, here is a table that recaps what I have been able to do so far (note that the dagesh is associated to the key "="). Some of the notes won't probably make sense to anybody else than myself.

On the dagesh:

אָב אֵם בֵּן הַר שָׁלוֹם רַבִּי אָמֵן שַׁבַּת רֵאשִׁית אֶרֶץ דָּבָר יוֹם

To do: print out Psalm 25 in Hebrew, along with a translation. Practice writing and recognizing the Hebrew letters; write them on flash cards.

Useful online reference: Learn to read Biblical Hebrew

Since it was not obvious for me to find how to type the Hebrew letters using the Tavultesoft Keyman keyboard with the Ezra SIL Unicode font just reading the docs, here is a table that recaps what I have been able to do so far (note that the dagesh is associated to the key "="). Some of the notes won't probably make sense to anybody else than myself.

| Name |

Letter |

Keyboard |

Sound |

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleph |

א |

Shift + . |

glottal stop [zero] |

|

| Bet |

|

|

|

|

| Gimel |

|

|

|

|

| Dalet |

|

|

|

|

| Hey |

ה |

h |

h [zero] |

When suffixed, makes the word

feminine. When prefixed, it is the definite article "the". |

| Waw |

ו |

w |

w [zero] |

Looks like a quarter note

(associate with "wav") |

| Zayin |

ז |

z |

z |

|

| Chet |

ח |

x |

ch as in Bach |

|

| Tet |

ט |

v |

t |

can't use "t" as key since this

is mapped to tav (below). Looks like a "tête". |

| Yud |

י |

y |

y [zero] |

attached to the end of a word

designates the possessive pronoun ("my") |

| Kaph |

|

|

|

|

| Lamed |

ל |

l |

l |

something like an L upside down |

| Mem |

מ ם |

m and M |

m |

vaguely resembles an "m" |

| Nun |

נ ן |

n and N |

n |

seems a shrinked version of a

persian nun |

| Samech |

ס |

s |

s |

reminds of the last part of a

persian sin |

| Ayin |

ע |

Shift + , |

[zero] |

It looks like a gamma, and

actually got translated into Gk as a γ (possibly because of an

original ghayn, retained e.g. in arabic), e.g. עמרה

-> Γομορρα |

| Pey |

|

|

|

|

| Tsade |

צ ץ |

c and C |

ts |

|

| Quph |

ק |

q |

q |

specular to a "q" |

| Resh |

ר |

r |

r |

specular to an "r" |

| Shin |

ש |

S |

|

|

| Tav |

|

|

|

|

On the dagesh:

- dagesh forte is the

point within a letter to indicate doubling. Example: המּלך hammelek,

the king

- dagesh lene is the point

within a letter to indicate stop instead of spirant for the six

consonants known as begadkepat,

i.e. ב ג ד כ פ ת. Because of the first rule above, this means that for

example בּ could be both "b" (stop) and "bb". Spiralized consonants

never occur doubled.

- mappiq -- to be

considered later

- a

- short, as in that: בַּ (b+dagesh+a)

- long, as in father: בָ (b+A). First word: father, אָב (easy: think of Gen 17:4-5, Abraham as "father" [Ab] of many nations -- whether this is philologically correct or not it doesn't matter here)

- reduced: בֲ (b+a+;)

- e

- short, as in elephant: וֶ (w+e - note lowercase e)

- long, as in grey: בֵ (b+E - note capital E). Mother: אֵם ; Son בֵּן (easy)

- reduced, as in help: אְ (shift+.+ ;). Note that when in the middle of a word it is silent.

- i

- long, as in machine:

בִ (b+i). One dot like our "i". Prophet: נָבִיא

- long, as in machine:

בִ (b+i). One dot like our "i". Prophet: נָבִיא

- o

- long, as in open: בֹּ (b+dagesh+o). Moses: משֶׁה (note that the dot over shin absorbes the dot over mem)

- u

- long, as in tune: בּוּ

(bu = b+dagesh+waw+dagesh)

- long, as in tune: בּוּ

(bu = b+dagesh+waw+dagesh)

אָב אֵם בֵּן הַר שָׁלוֹם רַבִּי אָמֵן שַׁבַּת רֵאשִׁית אֶרֶץ דָּבָר יוֹם

Sunday, October 24, 2004

Nominalism, gnosticism and orthodoxy

In the second chapter of Pagels' "The Gnostic Gospel" there is a most

interesting discussion on the troubles that early orthodoxy had to go

through in order to draw a clear line between canonical vs.

non-canonical

interpretations of the nature of God. The thesis is that how one

understands the nature of God brings about

political implications related to the relationship with the

ecclesiastical hierarchy. In particular, Pagels suggests that the way

gnostics understood the divine nature allowed them to break away from

the slogan "one God, one bishop".

The first point that sounds utterly modern is how Irenaeus describes the gnostics:

It is difficult for me at this stage to discriminate between apologetic and reality in Irenaeus' words. It seems clear, though, that what Irenaeus says is consistent with what I have read so far about gnosticism in general and valentinians in particular:

But another point struck my attention: in the Gospel of Philip we read

Pagels points out then that this distinction between words and reality has recently been suggested by Paul Tillich.

But it seems to me that well before Tillich such distinctions were made. The debates on nominalism in the Middle Age very much focused on this. As a matter of fact, Aquinas says:

Summa, Prima Pars, Quaestio XIII, A.1 ("Utrum aliquod nomen Deo conveniat"):

Categories: Church_History

The first point that sounds utterly modern is how Irenaeus describes the gnostics:

These men discourse to the multitude about those who belong to the Church, whom they do themselves term "vulgar," and "ecclesiastic. By these words they entrap the more simple, and entice them, imitating our phraseology, that these [dupes] may listen to them the oftener; and then these are asked regarding us, how it is, that when they hold doctrines similar to ours, we, without cause, keep ourselves aloof from their company; and [how it is, that] when they say the same things, and hold the same doctrine, we call them heretics? (AH, 3:15)So we see here again that one of the dangers of the so-called heretic movements was the apparent trouble to clearly distinguish them from the so-called orthodoxy. Cf. the notes on Marcion for another example, and specifically the worries of Cyril of Jerusalem.

It is difficult for me at this stage to discriminate between apologetic and reality in Irenaeus' words. It seems clear, though, that what Irenaeus says is consistent with what I have read so far about gnosticism in general and valentinians in particular:

[...] they describe to them in private the unspeakable mystery of their Pleroma. But they are altogether deceived, who imagine that they may learn from the Scriptural texts adduced by heretics, that [doctrine] which their words plausibly teach. For error is plausible, and bears a resemblance to the truth, but requires to be disguised; while truth is without disguise, and therefore has been entrusted to children. And if any one of their auditors do indeed demand explanations, or start objections to them, they affirm that he is one not capable of receiving the truth, and not having from above the seed [derived] from their Mother; and thus really give him no reply, but simply declare that he is of the intermediate regions, that is, belongs to animal natures. (AH, 3:15)This agrees with the strong predestination tones shown e.g. in the Treatise on the Resurrection; and this concept of predestination is probably by itself reason enough to explain the worries that orthodoxy had toward gnosticism from a political point of view.

But another point struck my attention: in the Gospel of Philip we read

Names given to the worldly are very deceptive, for they divert our thoughts from what is correct to what is incorrect. Thus one who hears the word "God" does not perceive what is correct, but perceives what is incorrect. So also with "the father" and "the son" and "the holy spirit" and "life" and "light" and "resurrection" and "the church" and all the rest - people do not perceive what is correct but they perceive what is incorrect, [unless] they have come to know what is correct. The [names which are heard] are in the world [...] deceive. If they] were in the eternal realm (aeon), they would at no time be used as names in the world. Nor were they set among worldly things. They have an end in the eternal realm. (53-54)Pagels suggests, and very rightly it seems to me, that once one understands that names point to a higher reality, it is a short step to conceive a completely different view of worldly institutions. So, if I know that what I mean by the word God is not what really God is and, even more importantly here, if I know that what I mean by the word church is not what the "real" church really is, it is understandable that I may regard with suspicion those, like the bishops and the priests of the early centuries, who built their spiritual (and political) power on the exclusive claim to be the the only authorized messengers of a reality that (to the gnostics) seemed very much entrenched in the (deceptive) world.

Pagels points out then that this distinction between words and reality has recently been suggested by Paul Tillich.

But it seems to me that well before Tillich such distinctions were made. The debates on nominalism in the Middle Age very much focused on this. As a matter of fact, Aquinas says:

Summa, Prima Pars, Quaestio XIII, A.1 ("Utrum aliquod nomen Deo conveniat"):

[...] Deus in hac vita non potest a nobis videri per suam essentiam; sed cognoscitur a nobis ex creaturis, secundum habitudinem principii, et per modum excellentiae et remotionis. Sic igitur potest nominari a nobis ex creaturis: non tamen ita quod nomen significans ipsum, exprimat divinam essentiam secundum quod est, sicut hoc nomen homo exprimit sua significatione essentiam hominis secundum quod est: significat enim euis definitionem, declarantem euis essentiam.And, in A.3 ("Utrum aliquod nomen dicatur de Deo proprie"):

Intellectus autem noster eo modo apprehendit eas, secundum quod sunt in creaturis: et secundum quod apprehendit, ita significat per nomina. In nominibus igitur quae Deo attribuimus, est duo considerare: scilicet, perfectiones ipsas significatas, ut bonitatem, vitam, et huiusmodi; et modum significandi. [...] Quantum vero ad modum significandi, non proprie dicuntur de Deo: habent enim modum significandi qui creaturis competit.This is not of course to say that Aquinas was "a gnostic": it is very clear that the aristotelian ontologism of Aquinas is different from that of the gnostics, with their pleroma, mythologies, and so on; still, the gnostic idea of nominalism (that entailed a conception of the world, of God, of the church, and of the function of its hierarchy so worrysome for Irenaeus and other church fathers) seems to have some similarity to what will later become the "orthodox one".

Categories: Church_History

Friday, October 22, 2004

Liturgy in 1 Clement

I recently received a personal email from a person doing his master

thesis on theology. He read my

notes on the First Epistle of Clement,

and about the statement

First of all, I wish to thank the author of the email. This is for me an excellent example of feedback. Then, I readily confess my ignorance on the matter: no, I do not have any specific literature to suggest -- but perhaps if anybody is reading this, he/she may be able to provide some pointers.

But the question seems too interesting to let it go without giving it some (albeit quick) thought. In the context of my notes, the statement about the liturgical use of the prayer at the end of the letter comes in the first place from the fact that the letter itself had well attested liturgical use (Eusebius, HE 4.23). Then, the form of the final part of the prayer is of intercession and benediction, reminding of other well-known liturgical formulae, e.g. Phil 4:23, 2 Cor 13:14, Rom 16:24, etc. The use of "Amen" to conclude the doxology seems also to suggest the double use of the prayer both as request for intercession on behalf of the author of the letter, and as communal prayer ("amen" will be said in this case by the congregation to respond to the prayer). Finally, other hints are provided about the general liturgical tone of the letter, one of the most clear being probably

Categories: Church_History

the letter seems to be a sermon, concluded by a solemn liturgical prayerhe asked whether I have some literature discussing criteria allowing one to distinguish between personal vs. liturgical prayer and/or whether I have my own personal criteria.

First of all, I wish to thank the author of the email. This is for me an excellent example of feedback. Then, I readily confess my ignorance on the matter: no, I do not have any specific literature to suggest -- but perhaps if anybody is reading this, he/she may be able to provide some pointers.

But the question seems too interesting to let it go without giving it some (albeit quick) thought. In the context of my notes, the statement about the liturgical use of the prayer at the end of the letter comes in the first place from the fact that the letter itself had well attested liturgical use (Eusebius, HE 4.23). Then, the form of the final part of the prayer is of intercession and benediction, reminding of other well-known liturgical formulae, e.g. Phil 4:23, 2 Cor 13:14, Rom 16:24, etc. The use of "Amen" to conclude the doxology seems also to suggest the double use of the prayer both as request for intercession on behalf of the author of the letter, and as communal prayer ("amen" will be said in this case by the congregation to respond to the prayer). Finally, other hints are provided about the general liturgical tone of the letter, one of the most clear being probably

And let us therefore, conscientiously gathering together in harmony, cry to Him earnestly, as with one mouth, that we may be made partakers of His great and glorious promises. (XXXIV)Cf Justin:

[...] the place where those who are called brethren are assembled, in order that we may offer hearty prayers in common for ourselves and for the baptized [illuminated] person, and for all others in every place [...] Having ended the prayers, we salute one another with a kiss [...] And when [the president of the brethren] has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings, all the people present express their assent by saying Amen. (1 Apology, LXV)If I had to investigate the function of liturgical prayer in the early church, I'd certainly have a look at liturgy in Judaism (e.g. references to, comparison with the Shemoneh Esrei) and how it influenced the church. In the context of the liturgical setting of 1 Clement, this seems all the more appropriate given the continuous references to the OT and it could also give, I think, some hints on developments in the institutionalization of the early church.

Categories: Church_History

Gk 2: prepositions

I think that, rather than trying to memorize "dry" prepositions and

associated cases, it

will be better for me to go back to the old method of memorizing some

key verses of the NT containing those prepositions. This has the

advantage of practicing to remember passages of the Scripture. And this

is, I think, quite important - incidentally, I never understood why,

back in school, we were asked to memorize some well known poems,

perhaps some

piece of literature [Dante has always been one of my favorites], and

this is all well and good, but never anything from the Bible (which

literature, history and philosophy classes mostly ignored, anyway).

Another example of dogmatic application of the (all too often

misinterpreted) concept of "laicism", I suppose.

I digged out examples and meaning mostly via the BDAG (not all meanings are reported here). I've tried to select the examples so that they remind me of a well-known episode or situation.

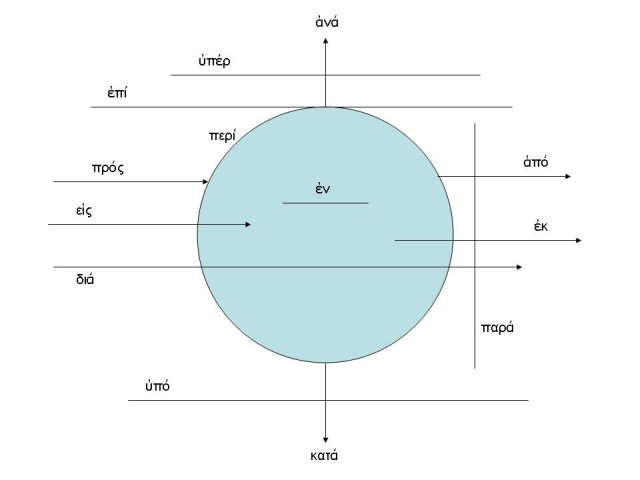

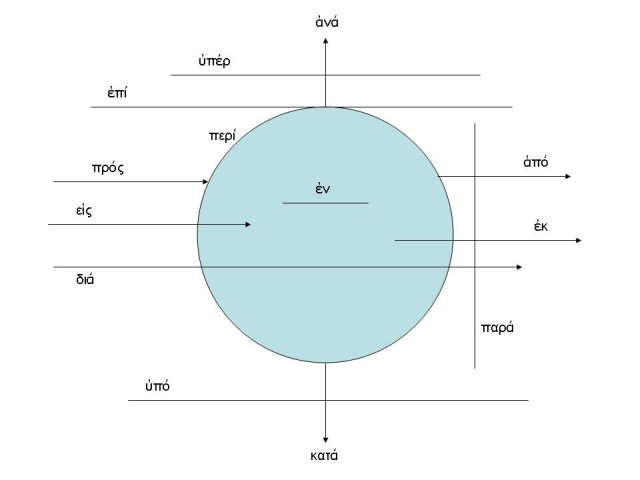

The full list: ανα, αντι, απο, δια, εκ, εις, εν, επι, κατα, μετα, παρα, περι, προ, προς, συν, υπερ, υπο. There is also a visual representation.

This is a visual representation of some of the prepositions:

Technology note: the client-side map of the picture above was created using the freeware program Map This.

I digged out examples and meaning mostly via the BDAG (not all meanings are reported here). I've tried to select the examples so that they remind me of a well-known episode or situation.

The full list: ανα, αντι, απο, δια, εκ, εις, εν, επι, κατα, μετα, παρα, περι, προ, προς, συν, υπερ, υπο. There is also a visual representation.

| Preposition |

Meaning |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ἀνά + Acc |

Lit.: up, upon

|

|

| ἀντί + Gen |

|

|

| ἀπό + Gen |

basic sense:

separation from someone of something |

καθεῖλεν δυνάστας ἀπὸ θρόνων καὶ ὕψωσεν ταπεινούς (Lk

1:52) |

| διά + Gen |

through |

πάντα δι' αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο, καὶ χωρὶς αὺτοῦ

ἐγένετο οὐδὲ ἑν ὃ γέγονεν (John

1:3) |

| διά + Acc |

through, but

primarily in the sense of "on account of,

because of, owing to" |

ᾔδει γὰρ ὅτι διὰ φθόνον παρέδωκαν αὐτόν (Matt

27:18) |

| ἐκ (ἐξ before

vowels) + Gen |

motion from the

interior |

οὐκ ἐρωτῶ ἵνα ἄρῃς αὐτοὺς ἐκ τοῦ κόσμου αλλ' ἴνα τηρήσῃς

αὐτοὺς ἐκ τοῦ πονηροῦ (John

17:15) |

| εἰς + Acc |

|

|

| ἐν + Dat |

being or remaining

within |

ἐν

ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λὸγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεὸν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ

λόγος. (John

1:1) |

| ἐπί + Gen |

upon, near (esp.

marking the position on a surface) |

ἐλθέτε ἠ βασιλεία σου, γενηθήτω

τὸ θέλημὰ σου, ὠς ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ

γῆς (Matt

6:10) |

| ἐπί + Dat | on, in, above,

immediate proximity |

καὶ ἐπέταξεν αὐτοῖς ἀνακλῖναι πάντας συμπόσια συμπόσια ἐπὶ τῷ χλωρῷ χόρτῳ (Mark 6:39) |

| ἐπί + Acc | on, toward,

specifying active motion, e.g. direction |

τετάρτῃ δὲ φυλακῇ τῆς νυκτὸς

ἧλθεν πρὸς αὐτοὺς περιπατῶν ἐπὶ τὴν

θάλασσαν (Matt

14:25) |

| κατά + Gen |

|

|

| κατά + Acc |

|

|

| μετά + Gen |

with, among |

καὶ ἧν μετὰ τῶν θηρίων, καὶ οἱ ἄγγελοι

διηκόνουν αὐτῷ (Mark

1:13) |

| μετά + Acc | after, behind |

καὶ

μεθ' ἡμέρας ἕξ παραλαμβάνει ὁ Ἰησοῦς τὸν Πέτρον καὶ Ἰάκωβον καὶ

Ἰωάννην τὸν ἀδελφὸν αὐτοῦ, καὶ ὰναφέρει αὐτοὺς εὶς ὄρος ὑψηλὸν κατ'

ἰδίαν (Matt

17:1) |

| παρά + Gen |

from beside |

καὶ πᾶς ὁ ὄχλος ἐζήτουν

ἅπτεσθαι αὐτοῦ, ὅτι δύναμις παρ' αὐτοῦ

ἐξήρχετο καὶ ἰᾶτο πάντας (Lk

6:19) |

| παρά + Dat | by the side of

(close association) |

ὀ δὲ Ἱησοῦς εἰδὼς τὸν

διαλογισμὸν τῆς καρδίας αὐτῶν ἐπιλαβόμενος παιδίον ἔστησεν αὐτὸ παρ' ἑαυτῷ (Lk

9:47) |

| παρά + Acc |

motion alongside |

καὶ παράγων παρὰ τὴν θάλασσαν τῆς Γαλιλαίας

ἑιδεν Σίμωνα καὶ Ἀνδρέαν τὸν ἀδελφὸν Σίμωνος ἀμφιβάλλοντας ἐν τῇ

θαλάσσῃ· ἧσαν γὰρ ἁλιεῖς (Mark

1:16) |

| περί + Gen |

concerning, as regards |

λέγων, Τί ὑμῖν δοκεῖ περὶ τοῦ Χρισοῦ; (Matt

22:42) |

| περί + Acc |

around, about |

καὶ ἧν ὁ Ἰωαννης ἐνδεδυμένος

τρίχας καμήλου καὶ ζώνην δερματίνην περὶ

τὴν ὀσφὺν αὐτοῦ (Mark

1:6) |

| πρό + Gen |

before |

Ἰδοὺ ἐγὼ ἀποστέλλω τὸν ἄγγελόν

μου πρὸ προσώπου σου (Matt

11:10) |

| πρός + Gen |

(on the side of, in the

direction of) from |

διὸ παρακαλῶ ὑμᾶς μεταλαβεῖν

τροφῆς, τοῦτο γὰρ πρὸς τῆς ὑμετέρας

σωτηρίας ὑπάρχει (Acts

27:34, only occurrence in the NT) |

| πρός + Dat |

(on the side of, in the

direction of) at |

καὶ θεωρεῖ δύο ἀγγέλους ἐν

λευκοῖς καθεζομένος, ἕνα πρὸς τῇ

κεφαλῇ καὶ ἕνα πρὸς τοῖς ποσίν (John

20:12) |

| πρός + Acc |

(on the side of, in the

direction of) to |

ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λὸγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεὸν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος. (John 1:1) |

| σύν + Dat |

with (association with) |

ἀπεθάνετε γάρ, καὶ ἡ ζωὴ ὑμῶν

κέκρυπται σὺν τῷ Χριστῷ ἐν τῷ

θεῷ (Col

3:3) |

| ὑπέρ + Gen |

on behalf of |

ὃς γάρ οὐκ ἔστιν καθ' ἡμῶν, ὑπὲρ ἡμῶν ἐστιν (Mark 9:40) |

| ὑπέρ + Acc |

over, above |

οὐκ ἔστιν μαθητὴς ὑπὲρ τὸν διδάσκαλον οὐδὲ δοῦλος ὑπὲρ τὸν κύριον αὐτοῦ (Matt

10:24) |

| ὑπό + Gen |

by |

τοῦτο δὲ ὅλον γέγονεν ἵνα

πληρωθῇ τὸ ῥηθὲν ὑπὸ κυρίου

διὰ τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος (Matt

1:22) |

| ὑπό + Acc |

under |

ἁμαρτία γὰρ ὑμῶν οὐ κυριεύσει, οὐ γὰρ ἐστε ὑπὸ νόμον ἀλλὰ ὑπὸ χάριν (Rom 6:14) |

This is a visual representation of some of the prepositions:

Technology note: the client-side map of the picture above was created using the freeware program Map This.

Sunday, October 17, 2004

Gnosticism and resurrection

I have been rereading Pagels' "The Gnostic Gospels"

off and on for a while now. It took me more than I had thought, but it

was (is) certainly time well spent. It is now time to recapitulate some

of the most important concepts.

Was Resurrection a symbol or an historical event?

Gnosticism gives a variety of answers. But orthodoxy has it that resurrection is not just about the "spirit", or the immortaility of the soul. Orthodox christianity maintains a literal interpretation. Cf. Tertullian, De Resurrectione Carnis, II.12:

The thesis of Pagels is that the selection of the literal interpretation of the resurrection cannot be explained in religious terms alone; it was selected because it served an important political function: to assert the authority of those who experienced the resurrected Christ (Peter being the first - although he was not, see Mary Magdalene), and of their legitimate heirs. A key point here is that the experience of seeing the risen Christ is closed with the Ascension. This is generally not what happens with the Gnostics, who insist that the Resurrection has to be interpreted in a somewhat symbolic way ("somewhat" meaning: not necessarily entirely symbolic) and therefore

The fact that it is not obvious to derive a literal interpretation of the resurrection from the biblical text seems admitted by Pius X who in 1907 in the decree Lamentabili Sane wrote

This treatise was probably written in the late second century. In it, resurrection is neither of the soul alone, nor of the literal flesh alone: resurrection is of a body that maintains certain "inner", and at the same time visible, characteristics (as in the resurrection of Elijah or Moses at Christ's transfiguration). This points to a dualistic doctrine of outer/inner that seems more elaborate than a simple dualism between spirit and flesh. In the words of the text:

Let's see what the key differences between the Treatise and orthodoxy are, then. According to the Treatise, one does not need to wait for Christ's parousia to be resurrected; one does not even need to wait for one's biological death: resurrection is in the present, once we consider ourselves as dead already, and therefore already participating of the resurrected state. Against this, see 2 Tim 2:17-18:

This realized eschatology sounds Valentinian. Cf. Tertullian, De Praescriptione Haereticorum:

The Valentinian character of the Treatise is reinforced by the explicit mention of the restoration of the Pleroma by Christ:

Interesting is the fact that, according to the gnostics, the resurrected Jesus does not show his bodily (earthly) form anymore and, even more interestingly, the perceived form depends on the subject observing that form. As the Gospel of Philip (perhaps written in the first part of the third century) has it:

Now, an important point is that orthodoxy prevailed probably also because aggregational forms of thought have many times proven to be more efficient (in terms of power collected, and of perceived authority) than individual solutions. Irenaeus is very clear: catholicism is defined by a consistent and universally accepted doctrine, whereas heretics exhibit a (sometime confusing and inconsistent) variety of thought systems.

Categories: Church_History

Was Resurrection a symbol or an historical event?

Gnosticism gives a variety of answers. But orthodoxy has it that resurrection is not just about the "spirit", or the immortaility of the soul. Orthodox christianity maintains a literal interpretation. Cf. Tertullian, De Resurrectione Carnis, II.12:

Animae autem salutem credo retractatu carere: omnes enim fere haeretici eam, quoquo modo volunt, tamen non negant.Where does this literal interpretation come from? In the NT there are episodes clearly meant to reinforce it: Lk 24:36-43, or John 20:27. At the same time, there are other stories, e.g. Mk 16:12: "Afterward Jesus appeared in a different form to two of them [...]", or Emmaus (Lk 24:13-32), or John 20:11-17 (Mary Magdalene mourning Jesus, seeing him and not recognizing him - immediately before the doubting Thomas episode!), that seem to suggest that the body of the resurrected Jesus was not the body that the apostles had known before his death.

The thesis of Pagels is that the selection of the literal interpretation of the resurrection cannot be explained in religious terms alone; it was selected because it served an important political function: to assert the authority of those who experienced the resurrected Christ (Peter being the first - although he was not, see Mary Magdalene), and of their legitimate heirs. A key point here is that the experience of seeing the risen Christ is closed with the Ascension. This is generally not what happens with the Gnostics, who insist that the Resurrection has to be interpreted in a somewhat symbolic way ("somewhat" meaning: not necessarily entirely symbolic) and therefore

- the resurrection is something that has to be obtained while living

- there is the possibility to encounter the risen Christ in the

present.

The fact that it is not obvious to derive a literal interpretation of the resurrection from the biblical text seems admitted by Pius X who in 1907 in the decree Lamentabili Sane wrote

The Resurrection of the Savior is not properly a fact of the historical order. It is a fact of merely the supernatural order (neither demonstrated nor demonstrable) which the Christian conscience gradually derived from other facts. (36)It is interesting to note that this position is not very different from the one proposed by the anonymous author of the Treatise on the Resurrection found at Nag Hammadi:

But if there is one who does not believe, he does not have the (capacity to be) persuaded. For it is the domain of faith, my son, and not that which belongs to persuasion: the dead shall arise!(although the Treatise makes it very clear that the teaching exposed are directly derived from the Word of Truth revealed by Jesus - but does not explain how)

This treatise was probably written in the late second century. In it, resurrection is neither of the soul alone, nor of the literal flesh alone: resurrection is of a body that maintains certain "inner", and at the same time visible, characteristics (as in the resurrection of Elijah or Moses at Christ's transfiguration). This points to a dualistic doctrine of outer/inner that seems more elaborate than a simple dualism between spirit and flesh. In the words of the text:

This is the spiritual resurrection which swallows up the psychic in the same way as the fleshlyThe debate of which "body" one would have after resurrection was one of the frequently asked questions of the time. See for example 1 Cor 15:35-53, which also suggests that resurrection is one of a spiritual type: σπείρεται σῶμα ψυχικόν, ἐγείρεται σῶμα πνευματικόν. (v.44) In this sense, there does not seem to be a lot of difference between this gnostic text and orthodox teachings (both ancient and modern) - although one could possibly argue that dualism in pauline anthropology was generally simpler than what is present in the Treatise.

Let's see what the key differences between the Treatise and orthodoxy are, then. According to the Treatise, one does not need to wait for Christ's parousia to be resurrected; one does not even need to wait for one's biological death: resurrection is in the present, once we consider ourselves as dead already, and therefore already participating of the resurrected state. Against this, see 2 Tim 2:17-18:

Their teaching will spread like gangrene. Among them are Hymenaeus and Philetus, who have wandered away from the truth. They say that the resurrection has already taken place, and they destroy the faith of some.Resurrection is a sort of enlightenment on the reality of things:

The world is an illusion! [...] [Resurrection] is the revelation of what is, and the transformation of things, and a transition into newness. (48)Note that this concept often lead Gnostics to theorize devaluation of the bodily form (and this can then range between the two extremes of absolute ascetism and consideration of bodily, esp. sexually, acts as utterly unimportant). As a confirmation of this, consider how much space Tertullian devotes in his De Resurrectione Carnis to explain the instrinsic value of the flesh.

This realized eschatology sounds Valentinian. Cf. Tertullian, De Praescriptione Haereticorum:

Aeque tangit eos qui dicerent factam iam resurrectionem : id de se Valentiniani asseuerant. (XXXIII,7)It has also to be said that this concept is linked in the text to strong predestination:

We are elected to salvation and redemption since we are predestined from the beginning not to fall into the foolishness of those who are without knowledge. (46)Obviously this self-consciousness of salvation, associated with the revelation of what really is, goes squarely against any claim to external spiritual authority. On the other hand, the concept of some realized eschatology can also be seen in pauline writings:

[...] having been buried with him in baptism and raised with him through your faith in the power of God, who raised him from the dead. (Col 2:12)

Since, then, you have been raised with Christ, set your hearts on things above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things above, not on earthly things. For you died, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God. (Col 3:1-3)

And God raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in the heavenly realms in Christ Jesus (Eph 2:6)But a common interpretation of these texts is that they mainly (or only) refer to the burial of sins, not to the full significance of resurrection.

The Valentinian character of the Treatise is reinforced by the explicit mention of the restoration of the Pleroma by Christ:

so that on the one hand he [Christ] might vanquish death through his being Son of God, and on the other through the Son of Man the restoration to the Pleroma might occur; [...] For imperishability [descends] upon the perishable [note that this verse is essentially 1 Cor 15:53]; the light flows down upon the darkness, swallowing it up; and the Pleroma fills up the deficiency. (44.49)But who can attain this resurrection, or the enlightenment on the true nature of reality? The gnostics thought that, outside the exoteric teachings offered to "the many", there were other and less public instructions:

[Jesus] told them, "The secret (τὸ μυστήριον) of the kingdom of God has been given to you. But to those on the outside everything is said in parables (Mk 4:11)And the Gnostics claimed that even Paul had some secret knowledge that he shared only with the "perfects" (translated as "mature" in NIV, NASB, NRSV): Σοφίαν δὲ λαλοῦμεν ἐν τοῖς τελείοις (1 Cor 2:6) Whether Paul really wanted to say what he says is debated among scholars.

[Jesus] replied, "The knowledge of the secrets of the kingdom of heaven has been given to you, but not to them. (Mt 13:11)

Interesting is the fact that, according to the gnostics, the resurrected Jesus does not show his bodily (earthly) form anymore and, even more interestingly, the perceived form depends on the subject observing that form. As the Gospel of Philip (perhaps written in the first part of the third century) has it:

Jesus took them all by stealth, for he did not appear as he was, but in the manner in which [they would] be able to see him. He appeared to [them all. He appeared] to the great as great. He [appeared] to the small as small. He [appeared to the] angels as an angel, and to men as a man. (57-58)Incidentally, the Gospel of Philip also supports the idea that resurrection has to be obtained while alive, and expands this concept in a rather obscure way:

Those who say that the lord died first and (then) rose up are in error, for he rose up first and (then) died. If one does not first attain the resurrection he will not die. (56)Again, this points to an unmediated way of perceiving Jesus, one that is tailored to each and every individual. This is the recognition that God's voice comes as a personal fact and is, it seems to me, not a small spiritual achievement. Pagels goes on to suggest that this individual understanding of and quest for Jesus can also be been in the very title given to Thomas ("didimus" = the twin brother): you, the reader, are Thomas, the brother of Jesus, hence this is said personally to each one of us:

[W]hile you have time in the world, listen to me [...] Now since it has been said that you are my twin and true companion, examine yourself and learn who you are, in what way you exist, and how you will come to be. [note the future] Since you will [future again] be called my brother, it is not fitting that you be ignorant of yourself. [...] [H]e who has not known himself has known nothing, but he who has known himself has at the same time already achieved knowledge about the depth of the all. (Book of Thomas the Contender writing to the Perfect, 138)I shall write something more later on about self-knowledge as knowledge of God in the Gnostics. The point here is that we have an attempt to achieve direct experience of God, and this direct experience can also be expressed in the concept of the resurrection.

Now, an important point is that orthodoxy prevailed probably also because aggregational forms of thought have many times proven to be more efficient (in terms of power collected, and of perceived authority) than individual solutions. Irenaeus is very clear: catholicism is defined by a consistent and universally accepted doctrine, whereas heretics exhibit a (sometime confusing and inconsistent) variety of thought systems.

[The Church] believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth. For, although the languages of the world are dissimilar, yet the import of the tradition is one and the same. For the Churches which have been planted in Germany do not believe or hand down anything different, nor do those in Spain, nor those in Gaul, nor those in the East, nor those in Egypt, nor those in Libya, nor those which have been established in the central regions of the world. (AH, I.10.2)And the only way to keep on having a consistent set of doctrines is therefore to faithfully follow the authority of the Apostles and of their successors. Heretics are then those who diverge seeking their own direct experience to God.

Categories: Church_History

Saturday, October 09, 2004

Gk 1: 1st and 2nd declension, article

In case it interests anyone, I am generally using Mounce's Basics of Biblical Greek, the associated workbook and the graded reader by the same author.

General notes:

7 vowels: α ε η ι ο ω υ

8 diphtongs: αι ει οι ου αυ υι ευ ηυ

3 improper diphtongs: ᾳ ῃ ῳ

Gamma nasal before 4 letters: γ κ χ ξ

5 elements for parsing: case, number, gender, lexical form, inflected meaning. Example: βασιλείας: accusative plural feminine, from βασιλεια, meaning "kingdoms".

1st and 2nd declension endings:

1) ι subscripts in D sng (and the final stem vowel lenghtens)

2) the α in N and A pl neuter absorbes the final stem vowel

3) the ω in G pl absorbes the final stem vowel

Note that 1st declension names with α as last stem vowel only keep α in G and D sng if the α in the stem if preceded by ε, ι, ρ. Otherwise, the α of the stem changes to η in G and D sng. For example,

(note ambiguity for ωρας in G sng and A pl -- the article helps: της ωρας and τας ωρας)

Some other examples:

Note that feminine nouns having η as the last stem vowel change it to α in the pl.

The article:

Note again the alternance between η and α in sng and pl feminine.

Note that the article is typically used in Greek also:

General notes:

7 vowels: α ε η ι ο ω υ

8 diphtongs: αι ει οι ου αυ υι ευ ηυ

3 improper diphtongs: ᾳ ῃ ῳ

Gamma nasal before 4 letters: γ κ χ ξ

5 elements for parsing: case, number, gender, lexical form, inflected meaning. Example: βασιλείας: accusative plural feminine, from βασιλεια, meaning "kingdoms".

1st and 2nd declension endings:

| 2 |

1 |

2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N |

ς |

- |

ν |

| G |

υ |

ς |

υ |

| D1 |

ι |

ι |

ι |

| A |

ν |

ν |

ν |

| N2 |

ι |

ι |

α |

| G3 |

ων |

ων |

ων |

| D |

ις |

ις |

ις |

| A2 |

υς |

ς |

α |

1) ι subscripts in D sng (and the final stem vowel lenghtens)

2) the α in N and A pl neuter absorbes the final stem vowel

3) the ω in G pl absorbes the final stem vowel

Note that 1st declension names with α as last stem vowel only keep α in G and D sng if the α in the stem if preceded by ε, ι, ρ. Otherwise, the α of the stem changes to η in G and D sng. For example,

| N |

ωρα |

δοξα |

|---|---|---|

| G |

ωρας |

δοξης |

| D |

ωρᾳ |

δοξῃ |

| A |

ωραν |

δοξαν |

| N |

ωραι |

δοξαι |

| G |

ωρων |

δοξων |

| D |

ωραις |

δοξαις |

| A |

ωρας |

δοξας |

(note ambiguity for ωρας in G sng and A pl -- the article helps: της ωρας and τας ωρας)

Some other examples:

| N |

λογος |

γραφη |

εργον |

|---|---|---|---|

| G |

λογου |

γραφης |

εργου |

| D |

λογῳ |

γραφῃ |

εργῳ |

| A |

λογον |

γραφην |

εργον |

| N |

λογοι |

γραφαι |

εργα |

| G |

λογων |

γραφων |

εργων |

| D |

λογοις |

γραφαις |

εργοις |

| A |

λογους |

γραφας |

εργα |

Note that feminine nouns having η as the last stem vowel change it to α in the pl.

The article:

| (2) |

(1) |

(2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N |

ὁ |

ἡ |

τό |

| G |

τοῦ |

τῆς |

τοῦ |

| D |

τῷ |

τῇ |

τῷ |

| A |

τόν |

τήν |

τό |

| N |

οἱ |

αἱ |

τὰ |

| G |

τῶν |

τῶν |

τῶν |

| D |

τοῖς |

ταῖς |

τοῖς |

| A |

τούς |

τάς |

τά |

Note again the alternance between η and α in sng and pl feminine.

Note that the article is typically used in Greek also:

- before abstract nouns, e.g. ἡ ἀληθεία

- before proper names, e.g. ὁ Ἰησοῦς

| οὐ |

Used when the following word begins with a consonant; example: ου δυναται πολις κρυβηναι επανω ορους κειμενη (Mat 5:14) |

| οὐκ |

Used when the following word

begins with a vowel and smooth breathing; example: ουκ ἐπ αρτω μονω ζησεται ανθρωπος

(Mat 4:4) |

| οὐχ |

Used when the following word

begins with a vowel and rough breathing; example: ουχ ὡς οι γραμματεις (Mat 7:29) |